|

Addressing Behavioral Health Needs of Men: Substance Abuse > Chapter 3 - Treatment Issues

|

|

3. Treatment Issues for MenIntroductionThis chapter describes specific issues facing men that can affect all elements of the treatment process, including the decision to seek treatment in the first place. Behavioral health counselors can anticipate barriers and better engage men in treatment by being aware of factors that influence why men abuse substances, which substances they choose, and the behavioral, social, and situational issues they may confront.The chapter begins by addressing co-occurring disorders—a major issue in the treatment of men—and goes on to examine social, behavioral, family, spiritual, and situational issues.

Treating Men for Substance Abuse: General ConsiderationsMany treatment approaches useful for men are the same that have been found useful for all clients. As noted in Chapter 1, most clients in substance abuse treatment are male, and most research into treatment methods has used populations that reflect the composition of treatment programs. Small adaptations can be made to improve treatment for men, such as ensuring that waiting rooms have decorations and reading material that appeal to men, and asking about client preferences regarding types of treatment (many menprefer more instrumental approaches, such as cognitive–behavioral therapy) and behavioral health service provider gender (see the discussion on therapist gender later in this chapter). Providers shouldalso recognize the motivations that typically bring men to treatment (such as criminal justice system involvement, referrals from other behavioral health resources, and family or work-related pressures, discussed in Chapter 5) and the possible resentment of treatment staff that can result. In treatment planning, consider approaches that have been found effective with men or with men who have particular characteristics (such as a highdegree of anger)—these, too, are discussed in Chapter 5.

The other considerations of which behavioral health service providers need to be mindful follow from an understanding of the factors that define masculinity and male roles in our society, which are discussed in Chapter 1. Men are expected to be independent, self-sufficient,stoic, and invulnerable. Consequently, they may have trouble identifying or expressing weaknesses or problems within treatment,which may be perceived as a lack of trust or an unwillingness to be open with counselors or fellow clients. Men often have concerns about privacy and need reassurance that treatment will pose no threat to their image or standing.They may also have trouble analyzing their own problems, particularly feelings related to those problems. This too is, in part, a reflection of men’s stoicism. Their need to be self-sufficient may result in a false sense of accomplishment or security in their recovery, which may manifest as unwillingness to follow through with continuing care or attend mutual-help meetings. Men are also expected to be competitive and,at times, aggressive. As a result, male clients may develop combative or competitive relationships with male treatment group members and staff or may appear resistant to others’ suggestions. They may resent being told whatto do, and so suggestions may need to be re-framed as conclusions that are reached collaboratively between client and counselor. Their need to prove themselves may extend into a number of different areas, including sexual accomplishment, physical domination (which can lead to violence), or competitive interactions with other clients (e.g., through the telling of war stories about their substance abuse). Treatment-Seeking Behaviors in MenWhen screening and assessing male clients for substance use disorders, behavioral health clinicians can take a number of steps to alleviate the discomfort men may experience when seeking professional assistance. Of course, establishing rapport and trust with the client from the start is essential. Although time restrictions are a reality, clinicians can make the most of the time they do have, even if only a few minutes. From their first contact with a male client, clinicians can be sensitive to the ways traditional male gender norms may be influencing the screening and assessment process. Certain male clients feel threatened by or uncomfortable with the help-seeking process,so clinicians in behavioral health settings can spend time initially developing rapport and establishing a connection before beginning screening and assessment. In some areas, this can be done by developing kinship: for instance, knowing a bit about where the client grew up, having a common understanding of the client’s work, or sharing an interest in are creational pursuit. When establishing kinship, though, counselors should take care not to transcend confidentiality boundaries or appear too intrusive in questioning.

Although male clients may have some common attitudes and behaviors based on gender role socialization, their personal definitions of masculinity and attitudes toward behavioral health services and interventions (e.g., therapy and assessment) will vary. As much as possible,clinicians need to determine the values, attitudes, and ways of behaving that define masculinity for specific clients and be sensitive to the fact that men who more strongly adhere to traditional male gender role norms might be more anxious than others about the process of seeking help (Good et al. 2005; Philpot 2001;Pollack and Levant 1998). Because men are generally ambivalent about seeking help for behavioral health problems, it is useful for clinicians to understand the circumstances that prompted a given man’s help-seeking behavior.“Why are you here now?” and “For help with what problem?” are useful questions the clinician can ask when beginning the screening and assessment process.Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) 35, Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Abuse Treatment (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment[CSAT] 1999b) offers useful techniques for working with clients who are ambivalent about entering treatment. [Question #28. Initial steps for clinicians in behavioral health settings include:] Many clients are resistant to entering treatment; although traditional concepts of substance abuse treatment emphasize personal responsibility for change, it can be useful for clinicians to accept some responsibility for engaging male clients in the helping process and motivating them for change (Marini 2001;Miller and Rollnick 2002). Clinicians can creatively engage male clients by asking what a client hopes to change via treatment or what he hopes to gain by beginning treatment. Men are often embarrassed or reluctant to self-disclose emotions, such as sadness or anxiety, so clinicians should consider acknowledging (e.g., through counselor self-disclosure)fears many men share about relationships,health, abandonment, career, and financial issues. Sometimes, self-disclosure is not warranted; therapists should not reveal personal information if they feel uncomfortable doing so or lack the training to do so properly (Forrest 2010). Clients’ reactions to clinician self-disclosure will depend on their expectations.Counselors should try to gauge those expectations, as research suggests that clients who expect self-disclosure will respond by giving more information when their expectations are met(Dixon et al. 2001). Self-disclosure, when done in the best interests of the client, can help move sensitive topics into the open, thus giving clients permission to begin talking about them. [Question #29. Which process,if done in the best interest of the client, can help to move sensitive topics into the open, thus giving clients permission to begin telling about themselves:] Advice to Behavioral Health Clinicians: Helping Men Get Comfortable With Seeking Professional Assistance

The engagement process can be conceptualized as a series of consecutive steps through which the client moves: screening, assessment,treatment planning, active treatment, and lastly, follow-up care (Good and Mintz 1990).Brooks (1998) suggests that, for men, clinicians assertively promote the need for substance abuse treatment and initiate the process one step at a time. The primary goal of each contact is to ensure that the client returns for his next appointment. Even if treatment is clearly indicated, it may be useful to first get the potential client to agree to an initial screening to determine whether further assessment is warranted. If it is, the next step is to get the potential client to agree to an initial assessment; next, to the completion of a comprehensive assessment; and finally, to a course of treatment. Men are typically socialized to be goal- directed and action-oriented (Pollack 1998a, b,2001), so emphasizing the immediate goal of each step in the screening and assessment process can be helpful, as can ending each screening or assessment session with a clear plan for what comes next. Offering something tangible at the end of an initial contact can also help.Depending on the circumstances that led to the initial screening or assessment session,something concrete (e.g., a letter of attendance, a telephone call to arrange a session with a significant other) can facilitate compliance with the next step. Giving men something to do to prepare for the next step supports their sense of confidence, control, and usefulness. Engagement Techniques for MenMotivational techniques can help behavioral health clinicians engage men in the process of screening and assessment (Miller and Rollnick 2002). Emphasizing the importance of free choice, even when there appears to be none,generally supports men’s need for autonomy.For example, even when men have legal mandates to seek treatment or are threatened with the loss of employment or a relationship, the decision to enter treatment can still be presented as voluntary. As much as a man might complain about his lack of choice, he often can still choose separation, legal sanction, or a job search over treatment. Men also can be offered choices about where and how screening and comprehensive assessment proceed; as much as possible, they should be offered choices and allowed to decide how the process will unfold. This process can be as simple as asking the man whether he would like to return next Tuesday or Wednesday or in the morning or afternoon. Emphasizing choices usually facilitates engagement. Similarly, although some treatment models emphasize assertive confrontation of denial, it may be useful, as Miller and Rollnick suggest, to avoid argument and circumvent resistance in a more subtle, less confrontational manner. For more on how to use Miller and Rollnick’s approach to motivate clients with substance use disorders, see TIP35 (CSAT 1999b). TIP 34, Brief Interventions and Brief Therapies for Substance Abuse (CSAT 1999a), discusses the use of brief strategic and solution-based therapies in substance abuse treatment, which also may be useful in motivating clients to address specific problems.

Advice to Behavioral Health Clinicians: Treatment Engagement Considerations With Men

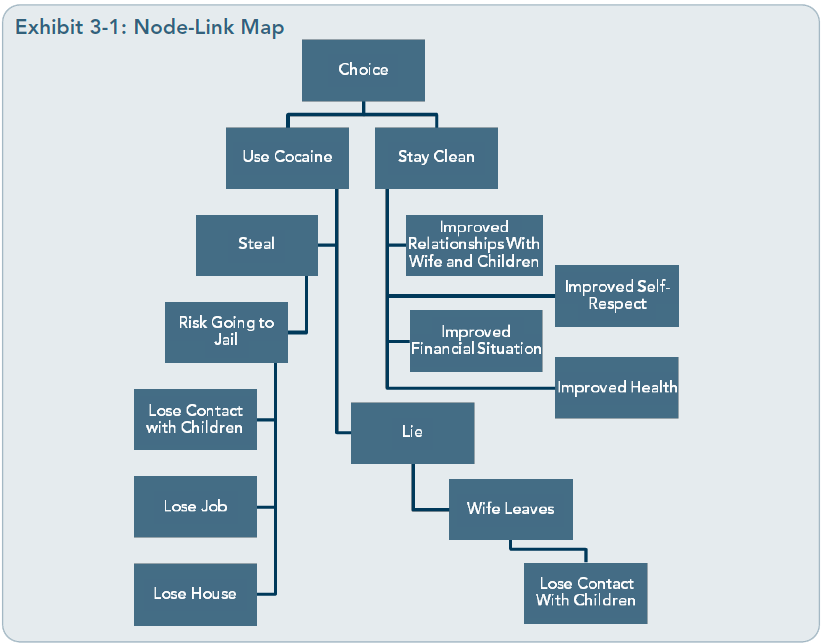

[Question #30. Confrontation about behavior and right/wrong issues always increases:] Directly acknowledging that men often have difficulty seeking assistance can be useful. Re-frame comments about failure or weakness by defining help-seeking behavior as a sign of strength and courage. Early in the process, the clinician can highlight ways that adherence to traditional norms about help-seeking behavior may conflict with or undermine other gender norms about being gainfully employed, a good husband, and a good father. Because men may be particularly uncomfortable with emotional expression or have difficulty identifying and understanding their own emotions early in treatment, the clinician should carefully monitor the emotional intensity of initial interactions, offering men time to compose themselves if needed. It may be useful to defer exploration of feelings until there is less anxiety about the helping process and a better working alliance. Avoiding competitive exchanges, comments, or questions that might provoke shame can likewise be helpful. In some settings, talking while walking can decrease the intensity of direct eye contact and allow clients to dissipate excess energy, which may help make some men more comfortable during initial sessions. Some men find it easier to look at their problems through a concrete visual representation(Halpern 1997). A variety of visual mapping techniques are available for clinicians to use.Timelines (Suddaby and Landau 1998), node-link maps (Czuchry and Dansereau 2003;National Institute on Drug Abuse 1996), and genograms (DeMaria et al. 1999; McGoldrick et al. 2008), among others, can be useful in treatment (Dees and Dansereau 2000). Eco-maps, similar to genograms, are graphic portrayals of personal and family social relationships (Rempel et al. 2007). Node-link maps help clients see, in concrete terms, the consequences of life choices. Exhibit 3-1 provides an example of a node-link map to help a client address a cocaine addiction. For more on genograms, see TIP 39, Substance Abuse Treatment and Family Therapy (CSAT 2004b). [Question #31. Visual mapping techniques are used by clinicians in treatment:] [Question #32.Eco-maps are graphic portrayals of personal and family social relationships True/False?] Counselors’ Gender: Some ConsiderationsLike ethnicity, race, religion, and culture,counselor and client gender can play a role in both the counselor’s and client’s experience of the therapeutic relationship. Gender colors the attitudes, feelings, beliefs, and interactions of both behavioral health counselors and clients. Therefore, it is important for treatment programs working with male clients to consider counselor gender. Both male and female counselors have their advantages, and programs need to consider the specific client as well as a range of other counselor-and program-related factors in assigning the best counselor for any given client. Counselors, too, need to be aware of gender dynamics and how they affect their practice.

Gender bias and stereotyping are among the most important issues that arise in substance treatment contexts with regard to the client’s and counselor’s gender. Other considerations that must be examined in the context of counseling men with substance abuse issues include the interplay between sexual orientation and gender, client preferences, the availability of male counselors, the appropriateness of raising the issue of gender with clients, and transference and countertransference issues.  Overcoming Gender Bias and StereotypingLike ethnic or racial bias, gender stereotyping is often ingrained in the subconscious by socialization, and even the most well-meaning clinician may be affected by it. Everyone has expectations about how men should behave,and some of these expectations are stereotypes that tend to limit behavioral health clinicians’ opportunities to provide the best possible treatment for their male clients.

How can clinicians overcome gender bias so that it does not negatively affect their work with men in substance abuse treatment? It is crucial that both male and female counselors explore their own biases and assumptions about men. Clinicians should ask themselves, “What is my first thought and immediate reaction to a male client who cries in a session? Do I directly or indirectly praise or encourage male clients who work long hours at the expense of their families? Do I assume that men respond to cognitive–behavioral therapy better than emotionally supportive therapy because men are rational?” Questions like these can help the clinician challenge deeply embedded assumptions and biases about men. In general, questioning one self helps overcome stereotypes and gender biases. When a male client walks into a clinician’s office, the clinician should be able to adopt a stance of curiosity about his or her own understanding and the client’s understanding of what it means for the client to be a man and how this identity is expressed in relation to his family, colleagues,friends, and the clinician. For example, many American men are raised to be independent and autonomous. Seeking or being mandated to treatment may feel like a weakness and affront to their sense of masculinity; however,such responses may not apply to a particular male client. Clinicians can inquire about such matters by saying, “I imagine that it may be difficult to ask for help because men are socialized to be strong and independent in our culture, but I am curious what it is like for you,specifically, to be here today.”The advice box below summarizes how both male and female counselors can address gender bias and stereotyping when working with male clients. Raising the issue of gender with clientsWhether or not clients can choose to work with a male or a female counselor, asking about their preference during initial assessment is a way of raising the issue of gender.Clients can be asked not just about dates of previous treatment if applicable, but also about the gender of their primary counselors in those episodes. Counselors can then use this information to inquire about clients’ past experiences with male and female counselors, what their preferences might be, and why. Exploring past counseling experiences and current preferences with regard to counselor gender is a nonjudgmental, empathetic way to let male clients know that their lived experience and preferences matter, even if it is not possible to match clients with their preferences. Johnson (2001) suggests including questions that address gender socialization and counselor gender preferences on the intake form and/or in the initial conversation with a male client.

Advice to Behavioral Health Clinicians: Addressing Gender Bias and Stereotyping While Working With Male ClientsFemale counselors

Male counselors

Client Transference Related to Counselor GenderTransference is an unconscious process in which individuals assign attributes from important persons in their past to persons in their present lives. In behavioral health counseling, transference generally refers to attributes clients assign to their counselors. Countertransference reactions are the attributes counselors assign (from their histories) to their clients. Transference and countertransference are not inherently good or bad, but both can potentially disrupt the therapeutic process if not recognized and monitored.

[Question #33. In behavioral health counseling, attributes that clients assign to their counselors refers to:] One of the most difficult issues to address in any counseling context is the sexualized transference that is likely when a female counselor works with a heterosexual male client or a male counselor works with a gay male client.In therapy, the counselor invites the male client to be open to his feelings, be vulnerable,and engage in a kind of intimacy that may or may not be present in other relationships in that client’s life. It is common and normal for the male client to feel emotional and/or sexual attraction for the counselor. Although this is a common occurrence, substance abuse treatment counselors may have received very little training in how to address client transference feelings, particularly sexual feelings. The following clinical scenario offers some options for addressing sexualized transference. [Question #34. One of the most difficult issues to address in any counseling context is :] Case example: Hank and JenniferHank is a married 32-year-old African American man with two young children. His drugs of choice were alcohol and marijuana; he entered treatment after his wife threatened to divorce him if he did not stop using. Hank describes his marital relationship as still shaky.He recently completed an intensive outpatient treatment program and was referred to individual counseling as part of his continuing care plan. He was given several counseling options and chose to make an appointment with Jennifer, a 28-year-old White American woman who has worked at the outpatient substance abuse clinic for 2 years. She is a lesbian who has lived with her domestic partner for 5 years.She is a licensed substance abuse counselor. Jennifer has been seeing Hank on a weekly basis for 3 months when Hank discloses, during a session, that he feels a strong attraction to Jennifer. The following is a brief excerpt of the conversation that ensues.

Jennifer: Hank, I really appreciate the fact that you are risking being so open with me about your feelings toward me. I want you to know that your feelings are normal and a common experience for people who come to counseling.I know this is your first time in individual therapy, so I am wondering how it is for you to hear me say that what you are feeling is normal. Hank: Well, it’s kinda a relief. I thought I was going crazy or that I’m really weird. Especially since, well . . . you know . . . because you’re gay. And you know I’m trying to make things right with my wife and I was worried that this meant that I don’t love her anymore. Jennifer: I understand your worry, but I want to reassure you again that it is very common for people to have all kinds of feelings, including sexual attraction, for their counselors. A good thing about these feelings coming up for you with me is that, because we have a professional relationship, there are boundaries that make it safe to talk about those feelings without acting on them. Hank:Really? Jennifer: Yes, really. In fact, think about how you have learned that you can talk about your desire to drink and how that helps you not acton your impulse to drink. You can talk about all sorts of feelings with me. I can help you learn how to experience and express those feelings in ways that support your goal to stay abstinent and that make things better with your wife and kids, instead of acting on your impulses in ways that aren’t consistent with your values and what’s important to you in your life. Hank: I never thought about it that way. That’s a relief. Jennifer acknowledges Hank’s attraction in a nonjudgmental way, establishes professional boundaries without shaming Hank, and uses his disclosure to reinforce the idea that feelings and impulses do not have to be acted out in negative ways, but can be expressed in ways that support his hopes and values. The key for the counselor is to understand that sexualized transference, which is not necessarily dependent on the gender or sexual identity of the counselor, is a common part of the counseling relationship and to view it as a potentially useful therapeutic opportunity to help the male client lessen the impact of shame in his life while modeling healthful ways of expressing and managing intense feelings. Countertransference dynamics for men working with menScher (2005) states that “countertransference issues are more significant with men working with men than women working with men” (p. 317). He suggests that countertransference issues for male behavioral health clinicians may be more subtle when working with men than when working with women. He states that “when power elements surface, the male therapist goes into competitive mode and does not easily give the competitiveness up; once he does, he begins to feel closer and therefore more vulnerable to the client, which raises homophobic issues and necessitates a pulling back” (p. 317). So the male counselor faces a dilemma when working with male clients.How can he be supportive, model vulnerability, and develop the intimacy required to establish a strong therapeutic alliance without pulling away from the male client due to internalized homophobia? How can he do so without becoming competitive and dictating treatment goals and plans from the position of the expert who has the objective, rational,right answer?

Certainly, one of the most important things male counselors can do is address counter-transference reactions in clinical supervision and consider them in their own practice. As discussed in Chapter 1, strong feelings of shame and inadequacy may arise whenever the male client consciously or subconsciously perceives that he is not living up to socially defined norms of male behavior, such as not asking for help and not being emotionally vulnerable. Male counselors also experience this dilemma when they open up to a clinical supervisor, and their experience of this vulnerability may be used to better understand clients’ feelings. Any strong emotional attraction the male counselor might experience for a male client should also be monitored and addressed in clinical supervision. Due to prescribed masculine gender norms, male counselors might be reluctant to bring up feelings of warmth,love, and emotional attraction for male clients.Clinical supervisors should be nonjudgmental and create a safe relational space for male counselors to bring up any strong reactions they might have to their male clients. If the male counselor is able to explore, with understanding and self-compassion, his own internalized beliefs about what it means to be a man, he will be in a much better position to help male clients challenge a story of masculinity that might not be their preferred way of being in the world. He will also be able to model a different kind of male behavior simply by being more open emotionally, less competitive and powerful, and working more collaboratively with clients. Countertransference dynamics for women working with menFemale behavioral health clinicians may have,at one time or another, been ignored or be littled by men in authority; sexually harassed;and/or subjected to domestic violence, child abuse, or childhood sexual abuse. As a result,two of the most potent countertransference issues female counselors may experience in working with men are fear and unresolved anger. A female counselor may subconsciously fear that her male clients will ignore, judge, or be little her, dominate or take over the therapy,or reject her efforts to help. One of the most difficult experiences women face in our society due to gender role socialization and culturally defined gender norms is a sense of being invisible. If a male client ignores the female counselor’s recommendations or be littles the efficacy of the treatment, shame and inadequacy may be activated. A female counselor’s subconscious anger may surface in the therapeutic relationship as cynicism, rejection of the client’s ideas about what works best for him,or being judgmental. Female counselors may also be sexually attracted to male clients. Such feelings should be normalized and addressed in clinical supervision, where supervisors can address gender differences between themselves and their supervisees to help them understand countertransference toward male clients.

Due to gender socialization, some female counselors tend to defer to the male client’s authority and his perception of his situation.Carlson (1981) suggests that “deference to male thinking, again reinforcing the traditional sex role for both, rarely assists the client in considering alternatives to his perception. Instead, it may only help to avoid the real problems and the potential for his growth” (p. 230).This can be a particularly challenging situation for female counselors in predominantly male substance abuse treatment programs. The female counselor must walk the line between being supportive and accepting and being willing to gently challenge the male client’s psychological defenses, such as denial and minimization of the reality that substance abuse is interfering with his life and relationships. [Question #35. The most potent countertransference issues female counselors may experience in working with men are :] Case example: Clinical team discusses male counselor/male client interactionThis behavioral health team consists of six clinicians ( Jim, Larry, Lillian, Jason, Mary, andKristen) and the clinical supervisor, Ken. The team is part of an intensive outpatient substance abuse treatment program at a major metropolitan hospital, which provides group therapy 5 days a week and individual counseling sessions twice a week. It is a mixed-gender program, but there is one women’s and one men’s group each week.

Jim brings up a clinical situation in group supervision. He has been assigned as the primary counselor for Kurt, a 45-year old bank executive who was referred to treatment through his company’s employee assistance program. Kurthad been involved in derivative trading and a series of high risk mortgages. He had been a heavy drinker most of his adult life; because of the stress of the economic downturn and his bank teetering on the brink of bankruptcy,Kurt has been getting drunk three to four times a week and recently started taking tranquilizers to deal with his anxiety. Jim states that this is Kurt’s first experience in counseling or treatment and that he is very resistant to Jim’s recommendation to attend Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings as part of his continuing care plan. The following discussion ensues. Jim: This guy really irritates me. I’ve been clean and sober for 20 years and he thinks he is such a hot shot executive. Every time I try to suggest something that might help him stay away from the booze and the pills, he comes at me with some story about how I don’t have a clue about what kind of stress he is under and that he knows what works for him . . . after all,he made it all the way up the corporate ladder to where he is today. I want to talk about whether or not we should consider shifting Kurt to another counselor. Maybe Mary or Kristen or Lillian could make more headway with him. Ken: What makes you think that it might be better for Kurt to work with a woman? Jim: Well, he seems to be more relaxed in the “Feelings Group” when Kristen is co-leading.And I think he really pushes my buttons. He reminds me of my older brother who was a varsity football player and won all kinds of awards. I hated football and was more interested in playing guitar in a local rock band.My father kept harping on me about how being in a rock band was for sissies. Now that Iam talking this through, it seems to me that Kurt probably feels the same kind of shame about not being a real man because he was forced to come to treatment. Asking for help was not something that was real big in my own family. Ken: Jim, I really appreciate your self-awareness here. It sounds like you are even beginning to feel less irritated and more compassionate toward Kurt. Jim: Yeah, I guess so . . . but I don’t know how to not react so strongly when Kurt gets so defensive. Ken: Well, I am wondering if you would be interested in briefly role-playing with Kristen.We could get the woman’s perspective on how to challenge Kurt’s defenses in a nonthreatening, noncompetitive way. What do you think? Jim: Well, I feel a little embarrassed about being in the spotlight. Ken: I can imagine. I am wondering if that’s some of your own fear about being vulnerable and thinking that because you’re a guy, you always have to have all the answers. Jim: You know me too well. Yeah, let’s do it. Ken sets up a role play in which Kristen plays counselor and Jim plays Kurt. Kristen is instructed to challenge Kurt’s competitive behavior in a nonjudgmental, non shaming way by pointing out the behavior and then asking,“What were the different expectations for boys and girls in your family?” This question begins a conversation about gender roles and expectations for Jim as the client. Inviting Kristen to take on the role of counselor allows all participants to indirectly challenge their own gender stereotypes and biases. By the end of the roleplay, Jim decides that he can continue to work with Kurt, feels a deeper appreciation for Kurt’s strategy of competitiveness as a way to hide his shame,and experiences renewed confidence for challenging Kurt’s behavior in a nonjudgmental way. He leaves the team meeting feeling reassured that he can ask his female colleagues for help with countertransference. Advantages of Female Behavioral Health Counselors in All-Male SettingsThe reality in most behavioral health clinical settings is that female counselors outnumber male counselors, and this disparity is even more striking when considering that male clients in substance abuse treatment significantly outnumber female clients (Lyme et al. 2008).Even in criminal justice settings, where the client population is typically all male, there are more female counselors than men (Ewing2001).

Both male and female medical patients talk more and provide more relevant information to female physicians (Bertakis 2009; Bertakis et al. 2003; Hall and Roter 2002). However, two studies (Farber 2003; Farber and Hall2002) found that gender did not predict disclosure among therapy patients. A small study (107 patients, 75 percent male) of a Dutch population ( Jonker et al. 2000) found that men in substance abuse treatment preferred female counselors (64.5 percent) and that most (58 percent) thought counselor gender played an important role in their treatment.However, when patients were asked to describe ideal characteristics for male and female therapists, those they listed were identical. Men may be more comfortable with female counselors for any number of reasons: they may feel more comfortable showing their weakness to female therapists, who they believe are less likely to judge them for their failures, real or imagined; they may believe that women are more sensitive and better able to address emotional problems; or they may have had negative experiences with male counselors in the past ( Johnson 2001). Some of these perceptions are based on real differences between common male and female counseling styles. Compared with male clinicians, female clinicians typically are more open to discussing relational issues and focusing on underlying process issues during treatment (Miller 1984).This approach may be helpful for some men,who generally tend to have difficulty dealing with their emotions in therapy (Levant 1995; Pollack 1994). Among physicians, women provide more counseling but men are more likely to address substance abuse (Bertakis etal. 2003). Another benefit to having female behavioral health service providers in facilities serving all-male populations is that they can model healthy male–female relationships for clients. Teamwork, cofacilitation of counseling, and collaborative working relationships between male and female staff members are of benefit to both the clinical team and clients because they provide positive role models for gender cooperation and communication. If clients see men and women interacting in healthy relationships with clear, nonsexist communication,they are likely to learn how men and women should act together. Potential Challenges for Female Counselors in All-Male SettingsFemale clinicians who work with men do face certain challenges. Each client, whether male or female, brings a set of individual experiences as well as a unique cultural background into the client–counselor relationship that will influence how that client responds to a counselor.For example, some male clients may see the male counselors as the real therapists having the real power in the organization, and may not allow their female counselors the same authority, power, or credibility. Some men have difficulty hearing their female counselors,which likely has to do with differences in how men and women communicate. Also, some men are not used to communicating openly with women.

Behavioral health programs need to be sensitive to the reality that some men who may be antagonistic toward or biased against women in positions of authority may not be able to form a healthy therapeutic alliance with female counselors. Rather than looking for ascapegoat or blaming the client for this, the institution should work with the client to devise a solution that will most benefit him in his recovery from substance abuse. In such cases, it may be best to pair the client with a male counselor. Advantages of Male Behavioral Health Counselors in All-Male SettingsMen tend to address concrete tasks more readily with male behavioral health counselors,which may work more effectively in a treatment setting that uses task-oriented brief therapy, solution-focused techniques, and motivational interviewing (Lyme et al. 2008); see the “Enhancing Motivation” section in Chapter 5 of this TIP for more information. Some literature supports the theory that men, particularly those from certain cultural backgrounds, disclose more thoroughly to other men. For instance, one study showed that Hispanic/Latino men were more willing to report risk-taking behavior to men than to women,and to older men than to younger men (Wilsonet al. 2002).

There are many potential benefits to having all-male group sessions, and a program typically needs male counselors to run these. Some well-known treatment centers, such as the Betty Ford Center and the Hazelden Clinic,will allow only male counselors to work with all-male treatment groups (Powell 2003). Potential Challenges for Male Behavioral Health Counselors in All-Male SettingsProblems can arise when men alone work as behavioral health clinicians in all-male settings. Male clinicians’ biases and sexism can reinforce negative male communication patterns. Many patients seeking treatment prefer female counselors, so an all-male staff can greatly limit the choices and potential treatment of clients who have such a preference.Male counselors are themselves subject to gender role strain and may have difficulty seeing clients in terms of individual or family pathology or as struggling with cultural issues,such as how to be a husband and father (Silverstein et al. 2002). Male clinicians and supervisors working with men who are gay need to be aware of their own biases, counter-transference, and level of awareness of gay development and gay culture (Frost 1998).

Recruiting Male Behavioral Health CounselorsThe first step for administrators in behavioral health settings assembling a trained, gender-sensitive male treatment staff is to understand their current staff makeup and the pool of providers from which they can expect to draw.The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) National Treatment Improvement Evaluation Study (Ewing 2001) examined staff members in treatment facilities that received SAMHSA funding. More than 800 counselors responded to the questionnaire. A majority of the counselors in each treatment setting (i.e., methadone, outpatient, short-term residential, long-term residential, and corrections) were women. In a larger study, Mulvey and colleagues (2003)used data from the retrospective study of treatment professionals to gain a profile analysis of the work force within the substance abuse treatment field. Demographic information from 3,267 participants demonstrated that most treatment professionals were White (84.5 percent) and middle-aged (between 40 and 55 years of age), and slightly more were female (50.5 percent) than male (49.5 percent). Further, it was noted that most professionals remain in the field for a considerable period of time and that approximately 80 percent had earned a bachelor’s or higher education degree. Most professionals were licensed or certified and provided treatment services to clients with racial and ethnic backgrounds different from their own.

It generally has been assumed that most clinical—and especially medical—education addressed men’s issues to the detriment of women’s issues. However, the 2003 SAMHSA Strategic Planning Initiative indicated that coverage of issues specific to men and substance abuse was lacking in most medical education programs (Haack and Adger 2002). Aspart of the 2003 SAMHSA initiative, training in substance abuse treatment, including men’s issues, became a mandatory part of all medical education. This project is a three-way collaboration involving SAMHSA, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse (AMERSA). SAMHSA and HRSA fund the project, which is administered by AMERSA. The project is known as “Project Mainstream.” All clients, regardless of gender, age, or culture,should have treatment tailored to their needs. Although a specialized credential for clinicians whose patients are mostly or all male may not be necessary, the consensus panel recommends that ongoing training be provided to all clinicians in the substance abuse field concerning the unique issues of both men and women. The number of female counselors is disproportional to the predominantly male client population seeking substance abuse treatment(Ewing 2001; Mulvey et al. 2003). Clinica lcenters staffed with both men and women of varying ages are better equipped to treat all clients. Agencies not committed to staff development, training, fair practices, and reasonable reimbursement can have problems in recruiting efforts, regardless of gender issues. Centers that need more male staff members may have to develop them from the groundup. A variety of distance learning and local certification resources are available, and cultivating talented counselors from among the many individuals in recovery who join the field may be an appropriate avenue for many agencies. For instance, SAMHSA has established 14 regional Addiction Technology Transfer Centers (ATTCs) along with a national center dedicated to identifying and advancing opportunities for substance abuse treatment, upgrading the skills of practitioners and health professionals, and disseminating the latest science to the treatment community.The ATTC Network Web site offers more information on ATTCs (http://www.nattc.org). Counseling Men Who Have Difficulty Accessing or Expressing EmotionsA significant number of men participating in substance abuse treatment and other behavioral health services have difficulty accessing or expressing emotions (Evren et al. 2008). These deficits can range from a profound absence of any emotion (sometimes referred to as alexithymia or being emotionally frozen) to a more common difficulty in recognizing and expressing specific emotions, such as anger, sadness,or shame. Sometimes, difficulty in handling emotions is a symptom of a mental illness, such as Asperger’s disorder, social anxiety disorder, or obsessive–compulsive disorder. Other times, it may result from transient or chronic stress, profound loss, or other environmental factors. For others still, difficulty with emotions may be a personality trait that has been with the individual since early childhood. All of these problems are likely to be exacerbated by substance use as a strategy for coping with unpleasant emotional states; finding new, positive strategies for understanding and expressing emotions is often necessary for a man’s recovery from substance abuse (Holahan et al. 2001). Some of the features of deficits in emotional expression include:

Case Example: JackJack is a 51-year old electrical engineer and computer software designer who recently completed the intensive phase of outpatient substance abuse treatment and has been referred to an ongoing therapy group for clients in recovery. His primary therapist in the intensive outpatient program felt the group would help Jack get in touch with his feelings. Jack readily acknowledges that he is a logical guy who sees emotions as having little utility, is uncomfortable around others who easily express emotions, and recognizes that his lack of emotionality has been a barrier in relationships. In his initial interview with the group leader, Jack comments that a primary reason for his heavy alcohol consumption (which began in high school) was that he felt more comfortable relating to others after drinking.He also recognizes that he was drawn to his occupation because it allows him to spend large amounts of time working alone and that he becomes uncomfortable in social and work situations when he cannot drink. In treatment,he found emotional expression in an all-male group difficult, and he is very apprehensive about being in a mixed-gender group now. He offered his primary counselor numerous reasons for not attending the outpatient group,but the counselor insisted that the experience would be good for him. He finally agreed to come for 12 visits (3 months). The following advice box gives some tips for Jack’s counselor.

Advice to Behavioral Health Clinicians: Addressing Male Clients Who Have Deficits in Emotional Expression

Anger ManagementAnger is a common problem for men with substance use disorders and can be exacerbated by the stress of early recovery. Because of men’s socialization, anger is one of the only emotions that many men feel comfortable expressing—thus, they often use it to cover up emotions (e.g., fear, grief, sadness) that they feel inhibited about expressing (Lyme et al. 2008).

A high level of anger, particularly trait anger, in men has been associated with substance use disorders and physical aggression (Awalt et al.1999; Giancola 2002b; Tafrate et al. 2002;Tivis et al. 1998). Trait anger refers to an individual’s disposition to experience anger in different situations, whereas state anger is the magnitude of the anger felt at a given time.According to a review of the literature, high trait anger is associated with a tendency to experience anger more frequently, more intensely, and for a longer period of time (Parrott and Zeichner 2002). The effects of alcohol on male aggression are most prominent in those who have moderate—as opposed to low— levels of trait anger (Parrott and Zeichner 2002). [Question #36. The magnitude of the anger felt at a given time is:] [Question #37. An individual’s disposition to experience anger in different situations is referred to as:] Men with anger problems are more prone to relapse to substance use (Kirby et al. 1995;McKay et al. 1995). A few cognitive–behavioral interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing anger in men who abuse substances (Awalt et al. 1997; Reilly and Shopshire 2000). Strategies used in one study to help subjects control their anger included the use of timeout, cognitive restructuring,conflict resolution, and relaxation training(Reilly and Shopshire 2000). Fernandez and Scott (2009) evaluated a 4-week-long cognitive–behavioral intervention for people in substance abuse treatment that was delivered in gender-specific groups; although the intervention had a high level of attrition (32 of 58 left before completion), it did reduce anger, especially trait anger. Motivational enhancement therapy or motivational interviewing may be even more effective than cognitive–behavioral approaches in reducing substance use for men with a high level of anger. Researchers analyzing data from the Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity Project found that, in general,clients who had high levels of anger did significantly better (in terms of days sober and drinks per drinking day) if they received motivational enhancement therapy rather than 12-Step facilitation or cognitive–behavioral therapy, but that the opposite held true for clients with low levels of anger (Stout et al. 2003). Karno and Longabaugh (2004), looking at the same data,however, concluded that what was more important than the type of treatment received was the level of counselor directiveness; they determined that clients who had high levels of anger did significantly better with counselors who were less directive (as the motivational enhancement counselors were). SAMHSA has produced an anger management curriculum with an accompanying client work book that provides a manualized 12-week group treatment for use in substance abuse treatment settings (Reilly and Shopshire2002). Exhibit 3-2 outlines some techniques used in this anger management intervention. Exhibit 3-2: Anger Management Counseling TechniquesThe main goals of anger management are to stop violence or the threat of violence and to teach clients ways to recognize and control their level of anger. There is no one correct way to conduct anger management counseling, but most interventions involve:

Given the nature of the topic, anger management counseling should only be conducted by trained clinicians. At the start of the first session, the clinician should explain to the group any policies on safety, confidentiality, homework assignments, absences and cancellations, time outs, and relapses.

SAMHSA curricula on anger management are available in two volumes—a therapy manual and a participant workbook—and can be ordered from the SAMHSA Store (http://store.samhsa.gov) or downloaded from SAMHSA’s Knowledge Application Program Web site (http://kap.samhsa.gov/products/manuals/index.htm). Source: Reilly and Shopshire 2002. Adapted from material in the public domain. [Question #38.The techniques for managing the physiological components of anger is:] [Question #39. The techniques that make clients aware of their self-talk while helping them actively stop and revise their counterproductive thought processes is:] Learning To Nurture and To Avoid ViolenceMany men with substance use disorders need to learn nurturing skills in their roles as husbands and fathers. Behavioral health counselors can teach and model affirming, caring, nurturing, forgiving, and having patience. Emotional vulnerability is critical if men are to be nurturing, loving, and caring husbands and fathers; it is important in many men’s recovery. For example, the 12 Steps of AA address vulnerability and openness to others. Counselors can suggest that men express vulnerability by engaging in nonstereotypical activities (e.g., creating art, poetry, or music; performing community service) instead of stereotypically competitive male activities like sports and work. Clinicians can also help men identify sports that they enjoy that promote cooperation, bonding, and commitment rather than extreme competition and violence.

[Question #40. Emotional vulnerability is critical if men are :] For many men, service is another essential part of recovery from substance abuse. Men who participate in mutual-help groups can be encouraged to engage in service activities related to those groups, and others can seek service opportunities in their communities or religious institutions, or with national or international groups. Service activities can be matched to men’s interests and skills. For example, men in building trades can work with Habitat for Humanity; men who like to cook can help prepare soup kitchen meals. Counselors should be sensitive to the kinds of service that would be most rewarding and therapeutic for the client and should not assume that all clients will benefit therapeutically from service work. Learning To Cope With Rejection and LossSome male clients may need to learn how to accept being told “no.” Consider this scenario: A man is at a social hour after work and asks a woman at the party out on a date. She is not interested and politely says “no” to him. He feels disappointed and either becomes more aggressive with her or returns to the bar for a pick-me-up to restore his ego. It is important for him to hear “no” not as a rejection of who he is but as the result of other factors (e.g., the woman’s interest in someone else). This insight could avert a relapse trigger for the client. The counselor may need to talk about and model for the client how to treat women with respect: taking “no” as an acceptable answer,giving women the power to accept or decline his invitation without intimidation, and experiencing her decision without it leading to substance use.

A man who is new to recovery may hear family members telling him “No, I won’t lend you my car” as an expression of doubt concerning his recovery. He needs to consider that there may be other reasons for not lending him the vehicle and, in any case, it does not reflect who he is today; it may take time for others to see that he has changed. There are many such situations, and men in recovery need to understand that being denied something is not a reflection of their own self-worth. Providers can introduce men to rituals that will help them deal with negative feelings, such as grief and fear, in a positive manner.Some examples include rituals for expressing grief, being vulnerable in the presence of other men, managing disagreements, and celebrating successes. Men can also observe the value of rituals in 12-Step programs, such as AA and Narcotics Anonymous. Counseling Men Who Feel Excessive ShameStigma and shame are strong obstacles to men’s seeking help, and research shows thatmen in substance abuse treatment often rate their level of shame as high (Simons and Giorgio 2008). Many men with substance use disorders and their families “ignore prevention messages, avoid treatment, [and] endure suffering and risk death daily for the simplest of reasons: They’re ashamed” (McMillin 1995, p. 3).

Social stigma tied to substance abuse, co-occurring disorders, other behavioral health problems, failure to meet society’s expectations, and other problems can cause intense feelings of shame among men. Shame, in turn,can cause men to avoid needed treatment and can cause their families and friends to deny a man’s substance use problem or try to control or cure him (Krugman 1995; McMillin 1995;Pollack and Levant 1998). Shame can also be a major impediment to growth in recovery. It can inhibit a man from looking inward, self-assessing, or experiencing personal deficits,resulting in white-knuckle abstinence and high risk of relapse. Different men will react differently to shame,and not all men in treatment will experience it(although it is very common). When clinicians are uncertain about a client’s degree or sources of shame, they can use an assessment instrument (see Chapter 2), and if the client is resistant to the notion that shame is affecting him, the clinician can share assessment results with him. For some men, shame can be an impetus for behavior change, whereas for others,it may impede change by fueling a desire to escape from the feeling rather than deal with its cause. Others respond to shame with secrecy, anger, denial, and/or hopelessness. Both Lewis (1971) and Scheff (1987) observe that some men externalize—holding others responsible for their actions—to shield themselves from experiencing shame. A client’s cultural orientation may also affect how he responds to shame. Anthropologists have proposed that certain cultures are shame based whereas others are guilt based; for example, for men from many Asian cultures,shame may be an even more significant feeling than for men from European cultures. There are also cultural differences in how individuals are expected to respond to shame. In some cultures, a man may be expected to publicly demonstrate his shame; in other cultures, a man may be expected to strike out in revenge at whomever caused him to feel shame. Stigma is different from shame; it results from social attitudes that label certain people, behaviors, or attitudes as disgraceful or socially unacceptable. Crocker and Major (1989) found that people experiencing stigma:

[Question #41. The feelings that result from social attitudes that label certain people, behaviors, or attitudes as disgraceful or socially unacceptable is: ] Cultural stigma can produce shame in many men with substance use disorders. Men who break gender norms, for example, can be subjected to stigma and experience shame as a result. Eisler (1995) describes gender role stress for men, which can result when a man feels that he has transgressed traditional gender norms. This stress can lead to shame if he perceives that he has violated the norms of a social group or failed to live up to the group’s expectations for appropriately masculine behavior. [Question #42. Men who break gender norms, violate the norms of a social group or fail to live up to the group’s expectations can be subjected to :] Substance abuse can lead to behaviors or situations that a man might find shameful or stigmatizing, and many of these relate to a failure to meet prescribed gender roles. Because of substance abuse, a client may have failed to support his family, lost an important job, or experienced detriments to his sexual performance or alterations in his pattern of sexual behavior. Medical conditions, such as HIV/AIDS and certain disabilities (especially physical), are also often stigmatized, as are lack of employment and homelessness; Nonn(2007) notes that men who are homeless or have low socioeconomic status have been “stripped of everything that qualifies a man for full participation in society” and thus belong to a shamed group (p. 282). Sources of stigma are discussed in greater detail later in this chapter. Interventions for ShameIn many ways, behavioral health clinicians are already addressing client shame (whether the client is male or female). Mutual-help group and modern substance abuse treatment processes both begin with a fundamental anti-shame message. A major reason for educating clients about the disease model of substance use disorders and their psychological, physiological, and natural histories is to help them overcome the shame they may have experienced in believing their illness to be a personal or moral failing. Clients also benefit from psycho education about shame and stigma. In mutual-help groups, the camaraderie of working with others to overcome the effects of substance abuse can be a powerful force for replacing shame with acceptance. Clinicians who are in recovery can also help eliminate the shame of having a substance use disorder by serving as powerful role models for recovering people learning to accept their disorder.

[Question #43. Pride in oneself is a major counter to shame.True/False?] Other interventions for shame are also already in use in most clinical situations. The most important way to help a client who is experiencing significant amounts of shame (see “Case example: Harry”) is to build a strong therapeutic alliance and create an atmosphere of trust in which the client feels comfortable openly exploring the sources of his shame. After building an alliance and exploring sources of shame, clinicians can help clients develop a realistic (i.e., not false) sense of pride, as pride in one self is a major counter to shame (Krugman 1998). Shame is likely to emerge in many interventions with men; clinicians should thus tailor treatment to avoid further shaming a client (Krugman 1998; Pollack 1998c). Case Example: HarryHarry is a 46-year-old man in an intensive outpatient substance abuse treatment program who has had numerous struggles in group andis seen by some counselors as uncooperative.He has resisted attending AA, tends to monopolize the group with long-winded stories of his successes, is defensive when confronted in group, and has not bonded well with other clients. He is also often sarcastic to other clients, but when they return the sarcasm, he either gets angry or withdraws and won’t participate in the group process. His behavior tends to alienate him from others, which increases his isolation in the program. In a recent group clinical supervision session, staff members discussed his case and concluded that shame motivates much of Harry’s disruptive behavior in group settings and that directly confronting his behavior makes him more defensive. Tips for counseling a client like Harry are given in the following advice box.

Advice to Behavioral Health Clinicians: Addressing Male Clients Who Are Disruptive in Group Settings Due to Excessive Shame

Counseling Men With Histories of ViolenceViolence and the use/abuse of certain substances (particularly alcohol and stimulants)are associated in numerous studies in many different contexts (Friedman 1998). Although violent behavior is not the sole prerogative of men, research has consistently found that men are more physically aggressive than women(Giancola and Zeichner 1995) and are much more likely to commit violent acts. For some men, acting in a violent manner may be a way to define their masculinity. Whether this response is simply the result of cultural factors or is due in part to biological differences is a question beyond the scope of this TIP. What is relevant, however, is that behavioral health service providers who work with men must be able to address violent behaviors in a client’s past and be prepared for violence in the present (both in and outside the treatment set-ting).This section addresses men’s involvement in violent behaviors; for more information on treating the short-and long-term consequences of exposure to violence, see the trauma section in Chapter 4.

Violence and Criminal BehaviorSome men may engage in criminal behavior as a way of showing adherence to a particular concept of masculine identity (Copes and Hochstetler 2003); others take risks that can make them the victims of violent crime for the same reasons (Thom 2003). Men are more likely than women to be the perpetrators as well as the victims of violent crime. In 2006,men were more likely to be the victims of every type of violent crime except rape, sexual assault, and purse snatching. In that same year, 26.7 per 1,000 men ages 12 and older were victims of violent crimes, whereas 22.7 women per 1,000 were victims of violent crimes (U.S.Department of Justice [DOJ] 2008). More than 60 percent of people treated in emergency rooms in 1994 for injuries resulting from violence were male (Rand 1997). In the case of murder, 77 percent of all victims and 90 percent of all perpetrators were male (Catalano2004). According to 2006 data, men were more than 3 times as likely to be violent offenders as women. When violent crimes were committed by a single offender, 78.3 percent of offenders were male (DOJ 2008). Throughout North America and Europe, women commit fewer than 1 in 10 assaults (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe2004). However, men who commit assaults while intoxicated are also more likely than women who do so to become involved in the criminal justice system as a result, although whether or not this reflects an existing bias remains to be determined (Timko et al. 2009).

Violent crime is also strongly linked with alcohol and drug use, with alcohol being the most commonly reported substance in cases of violent crime. In 2006, approximately 27.1 percent of victims of violent crimes reported that the offender was using illicit drugs (either alone or in combination with alcohol) at the time of the offense (DOJ 2008). Reports by violent offenders are similar, with 41 percent of those in jails, 38 percent of those in State prisons, and 20 percent of those in Federal prisons reporting that they were under the influence of alcohol at the time of offense (Greenfeld et al. 1998). People who abuse alcohol (whether determined by self-report or official data) are also more likely to commit property crimes (Andersson et al. 1999). In a Federal Government survey of State prisoners who were expecting a 1999 release, 83.9 percent tested positive for alcohol or drugs when they committed their offense, with 45.3 percent having used drugs at the time of the crime (Hughes et al. 2001). [Question #44. The most commonly reported substance in cases of violent crime is:] Certain substances are more likely to be associated with violent behaviors than others, but there is little research on how many substances affect violent behavior. However, enough data exist to support a link between alcohol use or abuse and being a perpetrator or victim of violence, especially among men (Stuart 2005).For men who are career criminals, substance use can be as important as criminal activity in defining masculinity (Copes and Hochstetler2003). Although different theories have been proposed for why men commit violent crimes, it does seem clear that gender roles hinder criminal behavior in women and enable it in men. Substances of abuse, especially alcohol, also seem to aid in removing inhibitions against violent and criminal behavior (Streifel 1997).Researchers postulate that men may expect alcohol to make them more prone to violence while women do not—a theory supported by Kantor and Asdigian (1997), who found that men were more likely than women to believe that alcohol increased irritability and feelings of power over others. Lisak (2001a) suggests that many men who perpetrate violence are themselves victims of violence, and that it “is therefore imperative to treat this underlying trauma” (p. 286). He notes that this process begins by demonstrating empathy for their pain, which helps these men feel their own past pain; being able to do so and to believe that they are worthy of sympathy is a first step toward empathizing with the pain of others. To reduce violent behavior in men, many behavioral health service providers have used cognitive–behavioral therapies to help men understand how criminal thinking patterns and irrational beliefs contribute to violent behavior. These approaches, often modeled onthe Oakland Men’s Project, typically teach communication skills to help men address problems in a more constructive manner. They are described in more depth in TIP 44, Substance Abuse Treatment for Adults in the Criminal Justice System (CSAT 2005b). Anger management is another useful adjunct for men trying to address violent behavior.Several studies show that many men with substance use disorders have high levels of anger(Awalt et al. 1999; Giancola 2002b; Parrott and Zeichner 2002; Reilly and Shopshire 2000; Tafrate et al. 2002). Anger can often lead to aggression and violence and can serve as a precipitant for relapse. Teaching men cognitive–behavioral strategies that help them manage their anger can reduce aggression and violence and possibly improve treatment outcomes (Reilly and Shopshire 2000). [Question #45. To reduce violent behavior in men, behavioral health service providers use:] SAMHSA has produced Anger Management for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Clients: A Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Manual (Reillyand Shopshire 2002) and the accompanying Anger Management for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Clients: Participant Workbook (Reilly et al. 2002), which detail an anger management intervention appropriate for substance abuse treatment settings. Interventions that address criminal thinking and improve communication skills may also prove useful in substance abuse treatment for men who have a history of violent criminal behavior. In particular, these approaches can help men understand how their substance use is related to criminal thinking patterns. Providers should note that the experience of violence can have a dissociating quality, and remembering past violence (whether one is victim or perpetrator, although typically perpetrators have also been victims of violence)can be a painful and problematic experience.Providers need to be sensitive to the difficulties clients may face in addressing violence in their past. (See the following sections on violence and abuse.) Domestic Violence and Child AbuseThe relationship between domestic violence and substance abuse is well documented (Caetano et al. 2001; Chase et al. 2003;Chermack et al. 2000; Cohen et al. 2003;Easton et al. 2000; Schumacher et al. 2003;Stuart 2005). The use of certain substances (e.g., alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamine) is associated with increased domestic violence,whereas use of others (e.g., marijuana, opioids)is not (Cohen et al. 2003). Some estimates suggest that up to 60 percent of men seeking treatment for alcohol abuse have perpetrated partner violence (Chermack et al. 2000;O’Farrell et al. 2004; Schumacher et al. 2003).A DOJ survey found that more than half of both prison and jail inmates convicted of a violent crime against a current or former partner had been drinking or using drugs at the time of the offense (Greenfeld et al. 1998).

A survey conducted by the National Committee to Prevent Child Abuse found that up to80 percent of child abuse cases are associated with the use of alcohol and/or drugs by the perpetrator (McCurdy and Daro 1994). Many individuals who abuse their children were themselves abused in childhood. The rate at which violence is transmitted across generations in the general population has been estimated at 30 to 40 percent (Egeland et al.1988; Kaufman and Zigler 1993). These probabilities suggest that as many as 4 of every 10 children who observe or experience family violence are at increased risk for becoming involved in a violent relationship in adulthood,either as perpetrator or as victim. [Question #46. Violence is transmitted across generations in the general population True/False?] Substance use is also associated with being the victim of domestic abuse for both men and women (Chase et al. 2003; Cohen et al. 2003;Cunradi et al. 2002; Miller et al. 1989;Weinsheimer et al. 2005). Other risk factors for both genders include being young, having a high number of relationship problems, and having high levels of emotional distress (Chase et al. 2003). [Question #47. The risk factors associated with the involvement of young people in violence and substance use are:] Violence between intimate partners tends to escalate in frequency and severity over time,much like patterns of substance abuse. Thus,identifying and intervening in domestic violence situations as early as possible is paramount. Staff members should understand relevant State and Federal laws regarding domestic violence and their duty to report. More information on the legal issues relating to domestic violence and duty to report can be found in TIP 25, Substance Abuse Treatment and Domestic Violence (CSAT 1997b), along with other valuable information on this topic.TIP 36, Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons With Child Abuse and Neglect Issues (CSAT 2000b), discusses child abuse and neglect issues for clients in treatment who have been abused as children and/or have abused their own children. Relapse can be a particularly high risk time for domestic violence, although it is unclear which event (relapse or domestic violence) precipitates the other. Regardless of causality, both issues need to be addressed. In the midst of a relapse crisis, it can be easy for the counselor to decide to deal with the violence at a later date. Several complications arise, however, as a result. Not addressing the violent behavior may imply that it is not significant or important. It also invites the client to sweep the event under the rug and not address it at a later date. Not addressing the violence may also signal to other family members that the violent behavior should not be brought into the open and discussed. Additional material on addressing domestic violence in counseling is offered later in this section. When issues like domestic violence or child abuse are discussed, all behavioral health clinicians should be aware of confidentiality laws and any exceptions to those laws that may apply in specific instances. Providers should also be aware of applicable Federal regulations (notably, the Confidentiality of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Patient Records laws contained in 42 CFR Part 2) and specific State regulations or laws (e.g., “Megan’s Laws”). Appendix B in TIP 25 (CSAT 1997b) and Appendix B in TIP 36 (CSAT 2000b) provide detailed discussions of these topics. In addition, the SAMHSA (2004) publication, The Confidentiality of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Patient Records Regulation and the HIPAA Privacy Rule: Implications for Alcohol and Substance Abuse Programs discusses these regulations as well as Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations that affect confidentiality of patient records. Men as victims of domestic violenceAlthough women are commonly perceived as the victims of domestic violence, the reality is that men can also be victimized by either male or female partners. In the National Violence Against Women Survey, 15.4 percent of men who lived with male partners and 7.7 percent of men who lived with female partners reported stalking, physical assault, and/or sexual assault by their partners (Tjaden and Thoennes 2000). Other studies, which contextualized domestic violence as family conflict rather than criminal behavior, report higher rates of female-on-male violence, although the types of violence perpetrated and the likelihood of it resulting in injury were inconsistent (George 2003). In a meta-analysis of physical aggression between opposite-sex partners, Archer(2002) found that men were more likely to cause injury to partners but that men still sustained one third of injuries resulting from such acts.

Studies of clients in substance abuse treatment have found high levels of intimate partner violence perpetrated by women against men.Cohen and colleagues (2003) interviewed 1,016 men and women in treatment for methamphetamine dependence: 26.3 percent of men (compared with 63.2 percent of women)reported that their partners had threatened them, and 26.3 percent of men (compared with 80 percent of women) reported that their partners had been physically violent. In a study of 103 women with alcohol use disorder seeking couples-based outpatient treatment, women were more likely to report having committed serious violence toward their partners (50 percent) than having been victims of such violence (22 percent), although this was not the case in a study of women seeking individually based treatment for alcohol abuse (Chase et al. 2003). It should also be noted that unmarried intimate partners appear to be more likely to commit violent acts toward one another than married partners (Straus 1999). [Question #48. Women were more likely to report having committed serious violence toward their partners than having been victims of such violence True/False?] Because stereotypes of masculinity (see Chapter 1) stress self-sufficiency and strength, men who have been abused by their partners may be even less willing to seek help than women.Additionally, there are fewer resources available for male victims of domestic violence than for female victims. The majority of domestic violence programs are designed for women,and many will not provide assistance to male victims; also, many men who are abused by their partners do not feel that the justice system will support them even if they do report the crime (McNeely et al. 2001). The problem is further complicated by traditional beliefs that men should be the head of the household and men’s fear of ridicule for not filling that role; the shame men may feel at disclosing family violence is compounded by the shame of not being able to keep their partners under control (Straus 1999). Often, providers presume that men in treatment should be screened as potential abusers but not as victims of domestic abuse, especially when the man’s partner is a woman (CSAT 1997b). Limited data are available on the rates of intimate partner abuse among gay male couples:for example, the National Violence AgainstWomen Survey (Tjaden and Thoennes 2000)found that men with male partners were twice as likely to experience domestic violence as men with female partners. Bartholomew and colleagues (2000) compared factors associated with partner abuse in heterosexual and gay couples, concluding that they were largely thesame and that substance use played a significant role in both situations. In a review of 19 studies that examined partner violence in gay and lesbian couples, Burke and Follingstad(1999) only found 3 that gathered data fromgay male couples and 1 that extrapolated data on rates of abuse for heterosexual men. Still,these limited studies suggest that men in same-sex relationships are at least as likely to experience violence from their partners as men in opposite-sex relationships. [Question #49. Men who have been abused by their partners may be even less willing to seek help than women because:] Treatment and referral for domestic violenceFor men who have a history of either perpetrating or being victimized by domestic violence, collaboration with and referrals to domestic violence intervention programs can facilitate their substance abuse treatment. At the same time, behavioral health service providers need to be aware that certain therapeutic interventions (particularly couples or family therapy) can increase the likelihood of further domestic violence and should not be used with clients who have such a history. In some States, standards for domestic violence treatment programs warn against couples counseling as an initial intervention, and some standards regulate what individual treatment improvements need to occur prior to any couples counseling. Interventions designed to reduce domestic violence without addressing substance abuse have proven to be minimally effective (Stuart 2005).